DNA exists in both material (molecular) and dematerialised (genomic data) forms. It also has the paradoxical status of encoding information regarded as an incontestable expression of individual identity, requiring data privacy, whilst simultaneously being a bodily material that is shed copiously into the world, via a multitude of routes, and in rare cases can be extracted and sequenced from bodily remains thousands of years later.

This excerpt from an abstract Jimmy, Carolyn and I submitted for the ANAT SPECTRA symposium in Melbourne in 2022 describes a paradox that intrigues me – that DNA is packaged away securely in cell nuclei, significant enough as a marker of individual identity to require data protection protocols once sequenced, whilst as a cellular material DNA is shed casually everywhere, all of the time, wherever we go.

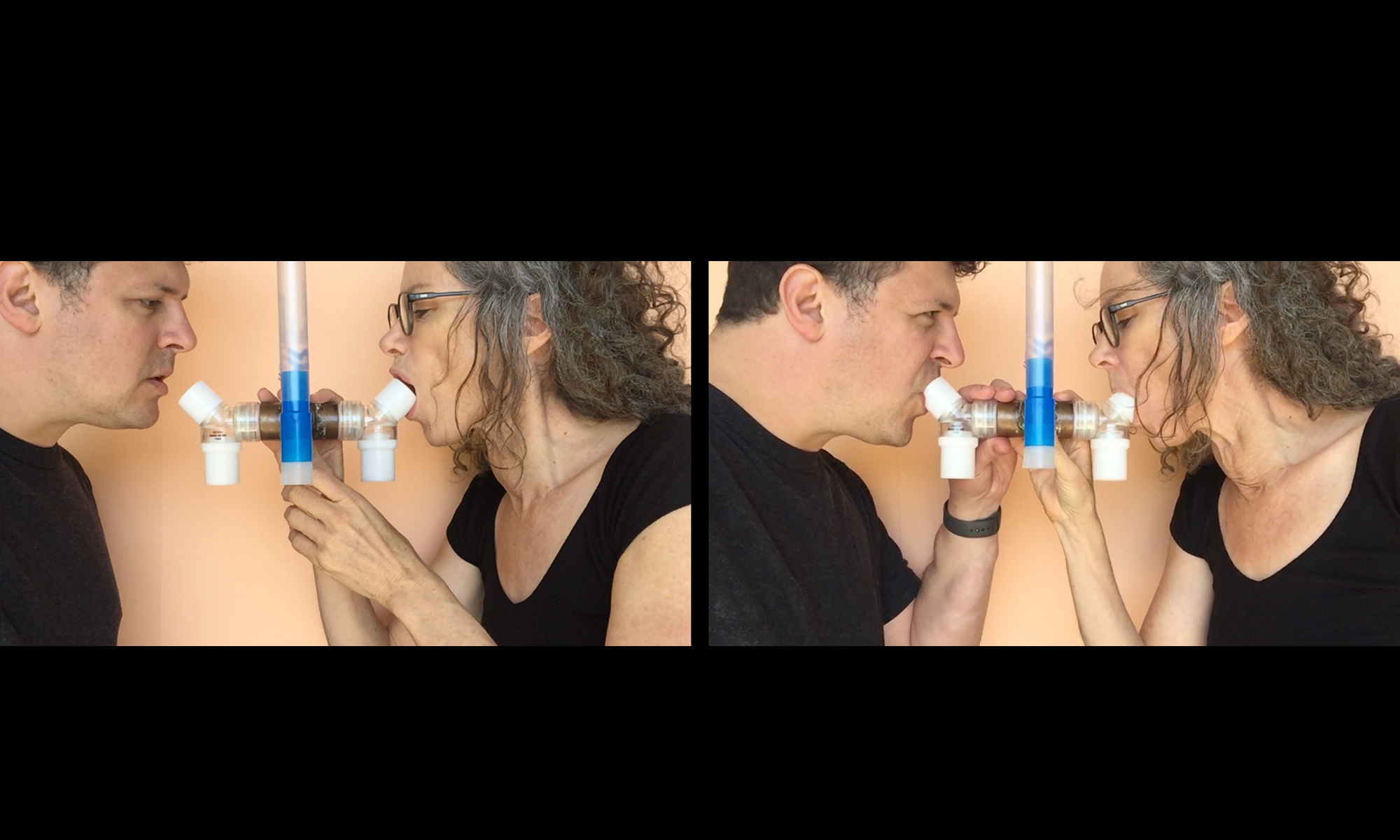

Exhaled breath DNA

DNA is shed into the world with sloughed off skin cells, hairs that drop from our heads, body fluids that leave our bodies such as saliva, and as I learn from Jimmy, in tiny microscopic droplets of vapourized fluid when we breath out. Our exhaled breath DNA includes our own DNA alongside DNA from our respiratory tract microbiome – bacteria, fungi and viruses – packaged inside exhaled cells and as fragments of cell-free DNA.

These tiny DNA projectiles ride the invisible roller coaster of air currents that drift from our mouths, and are in turn inhaled by human and non-human others in our vicinity. And we, of course, inhale the tiny DNA droplets that others exhale. It’s wondrous that this most nebulous of materials – breath – is the vehicle for this rather strange and promiscuous interpersonal and interspecies exchange of DNA material. There’s something humorous and repellent about these unwitting and unseen exchanges of DNA. It’s also philosophically intriguing, resonating with Margrit Shildrick’s microchimerism, perhaps enacting some kind of transient nanochimersim or ephemerchimerism, demonstrating the fluidity and fecundity of DNA and the unbounded character of our bodies. What Shildrick writes about microchimerism applies equally well to exhaled breath DNA:

In other words, the project is to elaborate a hitherto unregarded network of relations that dispenses with the boundaries of singular location and time and reimagines the concept of living outside oneself. In an embodied hauntology, the other is always within, but equally the self (if we can still call it that) externalises its becoming (Shildrick, 2019, 16-17).

Exhaled breath DNA raises complex ethical questions. If we shed our DNA copiously around the world, leaving potentially ‘readable’ traces of ourselves, what might happen if the costs of DNA sequencing continue to plummet, and fast DNA sequencing in real time becomes technologically and economically available at a consumer level? A nanopore DNA sequencing technology developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies produces DNA sequence reads in real time, with very small portable devices, that are a fraction of the cost of setting up a full sequencing lab. In the current moment mining of our online data and AI technologies such as face recognition software are more immediate threats to our privacy and surveillance, but the 1997 film Gattaca played out a scenario of constant genomic surveillance and its use in eugenic programs as a futuristic dystopian sci fi.

Viral shedding

During the current pandemic we’ve become all too familiar with a related phenomenon – viral shedding. Viruses are strange life forms consisting of some nucleic acid material (DNA or RNA) packaged inside a protein coat. Viruses are tiny and so simple that they lack the cellular machinery to reproduce themselves. Rather they rely on inserting themselves into the cells of hosts and redeploying their host’s cellular machinery to reproduce themselves. They evolve in highly specialised ways that target particular host species, which is why a human virus may be completely benign to other species we live in close proximity to, such as our pets. However viruses frequently jump species barriers, as we know from ‘swine’ flu, ‘avian’ flu, ebola virus, lyssavirus and perhaps COVID-19 (the origins of COVID-19 remain unconfirmed and contested).

Viruses like COVID-19 are exquisitely evolved to deploy our out-breaths as a taxi service that can transport them to the warm, moist, embracing environs of other human respiratory tracts in our vicinity, where they can start a new cycle of infection and reproduction.

This extract from an article in The Conversation explains viral shedding:

When you’re sick with a virus, the cells in your body hosting the infection release infectious virus particles, which you then shed into the environment. This process is called viral shedding.

For SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, shedding primarily occurs when we talk, cough, sneeze, or even exhale. SARS-CoV-2 can be shed in a person’s stool too.

Research shows shedding of infectious SARS-CoV-2 begins before a person starts displaying symptoms, and peaks at or just after symptom onset (usually four to six days after infection).

Shedding can continue for several weeks after a person’s symptoms have resolved — there’s no standard time frame.

Research has identified shedding of infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus particles from up to eight days after symptom onset in hospitalised patients, to up to 70 days after diagnosis in an immunocompromised person.

ANAT SPECTRA Abstract: Helen Pynor, Jimmy Breen and Carolyn Johnston. 2021. ‘DNA as molecule, DNA as data: Liminal entities, radical porosity, and the limits of legal and ethical practices of care’ (Working title). Abstract submitted for the ANAT biennial symposium SPECTRA, Melbourne 2022.

Shildrick, Margrit. 2019. ‘Micro(chimerism), Immunity and Temporality: Rethinking the Ecology of Life and Death.” Australian Feminist Studies 34 (99): 10-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2019.1611527